The Once and Future Pug

Pug puppy: 3-month-old male, nicknamed S’more. Born on Valentine’s Day, he’s ready to love you and your family! One of a litter of 4. He’s all pug: big brown eyes, button nose, adorable smushed face, and a perfect double corkscrew tail. Fawn-colored coat, silky ears. Pugs are famous for being affectionate and laid back. Good with kids, dogs and cats, and great for cuddling. Playful but low maintenance. Not barkers. Great house or apartment dog! $1800. Puppies have been dewormed, received their first set of vaccinations, and will be microchipped. Health documentation provided. AKC registered parents. Is S’more your new fur baby?

Of course! Who can resist a pug? “I love pugs,” a veterinary behaviorist says in The Animals Among Us, but then adds, “That’s why I don’t own one.”

We’ve bred pugs to be cute. They trigger the “cute response,” an inherent, positive, and unconscious reaction to babies. (See “Your Brain on Babies.”) In evolutionary terms, this caretaking response makes great sense. What’s surprising is that our brains respond to baby-like features even when they’re not human. This helps explain the appeal of puppies and other baby animals. In a shelter situation, the dogs with more—to use the scientific term—paedomorphic faces and expressions are more likely to get adopted. Simply put, pugs are extra appealing to us humans.

In the United States in 2023, the pug was the 35th most popular breed out of 200, according to the American Kennel Club. That adds up to a lot of pugs. As with any popular breed, there are national and regional pug clubs, pug breeders all across the country, and rescue organizations dedicated to pugs. No surprise, kids’ books abound—Captain Pug (along with Pirate Pug and others), Pugs Are the Best (as well as Dachshunds, Poodles, Golden Retrievers, and more), and a best-selling series about Pig the Pug. All are available at my local library. And, of course, there’s pug paraphernalia: greeting cards, tee-shirts, plush toys, fridge magnets, and more. The website of the Pug Dog Club of America describes the pug as “eager to please, eager to learn and eager to love. His biggest requirement is that you love him back.”

Why would a veterinarian who loves pugs refuse to own one? Because the breed’s in crisis. The Royal Veterinary College sponsored a large cross-sectional study of data drawn from electronic primary veterinarian records across the United Kingdom. It was the largest study of the health of pugs to date and compared and contrasted the health of pugs with all non-pugs in the study. Pugs experienced significantly more health problems—especially eye, breathing, and skin disorders—than non-pugs. This led the authors to conclude in 2016, that “Highly differing health profiles between Pugs and other dogs in the UK suggest that the Pug has diverged substantially from mainstream dog breeds and can no longer be considered as a typical dog from a health perspective.” The pug has reached a tipping point: Breeding has created an adorable dog that is almost guaranteed to suffer.

In a chapter on the welfare of dogs in The Domestic Dog, the authors identify two kinds of “genetic welfare problems” created through breeding. The first occurs “as consequences of deliberate selection for accentuated anatomical features.” The second occurs when inbreeding allows an unhealthy recessive genetic mutation to become “prevalent” in a breed. The pug is affected by both, but especially the first.

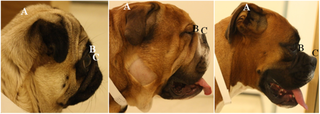

Precisely what we find so appealing about pugs—the large rounded head, pudgy cheeks, big eyes, little nose—damages their health. They are flat faced, or brachycephalic (from the Greek, short + head; brah-kah-suh-fa-lik). We have deliberately bred for a genetic mutation that keeps the skull from developing normally. This is “selective arrested development,” as John Bradshaw explains in Dog Sense. Without understanding the mechanism or consequences, breeders selected for this mutation because of its cute look. As the muzzle skeleton changes, the rest of the soft tissue within the dog’s mouth, nasal passages, larynx, and windpipe develops more normally, with the end result that too much tissue is compressed into too little space. Brachycephalic breeds—especially pugs, French bulldogs, and English bulldogs—frequently develop Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS), and especially as they age. A healthy young pug may become an unhealthy, miserable adult dog.

In BOAS, the nostrils narrow or even collapse inward, as does soft tissue inside the nose; the soft palate extends into the airway itself, obstructing airflow; and other soft tissue is pulled into the windpipe where it also restricts the flow of air. At the extreme, as a dog tries harder to pull air into its lungs, the airway collapses and the dog suffocates. In Alexandra Horowitz’s Our Dogs, Ourselves, Amy Attas, a veterinarian who rescued a pug with BOAS, offers an analogy: “It’s like breathing through a straw.” I tried it. It’s exhausting, even for a few minutes. Attas had to perform corrective surgery on her adopted dog’s nasal passages, soft palate, and sacs in the larynx to enable her dog to breathe more naturally.

The pug has by far the shortest head and muzzle.

In 2015 another study found that the risk of BOAS “increases sharply in a non-linear manner as relative muzzle length shortens.” This puts the pug, with its radically foreshortened muzzle, at particular risk. BOAS isn’t a bug in the system but a feature. Owners get used to pugs’ wheezing, and often believe “it’s normal for the breed.” But wheezing in any dog is abnormal, just as it is in a person. Once we can hear a dog’s wheezing, the dog already has moderate BOAS. Even a dog that isn’t diagnosed with BOAS may chronically get too little oxygen, with wider effects on its health. What’s amazing about pugs, and dogs in general, is that they carry on. They don’t show their suffering unless it’s acute.

Pugs also have eye, skin, dental, and spinal issues. According to the comparative 2016 study of veterinary records, in addition to BOAS, pugs are more likely than other dogs to suffer from ulcerations of the cornea (13 times), infections in their skinfolds (11 times), retained baby teeth (4.3 times), and obesity (3.4 times; this is attributed to their tendency to overheat due to difficulty breathing and so not to exercise as much). The reshaping of the skull also affects the shape of their eye sockets, making their eyes prone to injury and even displacement. Some have trouble closing their eyelids all the way.

Their shortened skulls are not the only problem. Their corkscrew tails are produced by misshapen vertebrae at the base of the spine, and the genes that create this effect in the tail can also cause misalignment of the spine and misshapen vertebrae elsewhere. This spinal condition can result in pain, unsteady walking, an abnormally shaped back, weakness, muscle deterioration in the back legs, and incontinence. In a 2016 article in The Guardian, a veterinarian calls pugs “anatomical disasters.”

Humans and dogs have lived together for many, many thousands of years. Early dogs may have resembled dingoes, which weigh 26-44 pounds, stand about 24 inches tall at the shoulder, have erect ears, long snouts, straight tails, and coats that range from sandy colored to black. In other words, a pretty generic medium-sized dog. Humans gradually found uses for this social, highly flexible species—tracking, guarding, hauling, herding, pointing, retrieving, ratting, and hanging out with humans. Ancient breeding choices were driven by these functions, and the function gradually shaped the dog’s form—and some other characteristics, such as color or ear shape, came along as part of the genetic package. An especially good guard dog, which was large, highly alert, and had a loud bark, might be crossed with another still larger dog. Distinct types of dogs gradually developed. For example, a large guard dog, called a mastiff, appears in English records starting the 15th century. This historic mastiff shares characteristics with our modern mastiff breeds—large, powerful, and short-haired—but it was not a breed by our modern definition. Horowitz describes a pragmatic process in the past: “These would have been breeds that formed more or less naturally, with humans merely keeping around and feeding the ones they liked and culling or casting off the ones they did not.”

Some types of dogs go way back. The ancient Greeks and Romans kept, pampered, and loved small white dogs. Aristotle wrote about one he called a Melitaean dog. Is this the Maltese? For some, a few facts are all it takes to jump to big conclusions, as the American Kennel Club (AKC) does on its website: “The tiny Maltese…has been sitting in the lap of luxury since the Bible was a work in progress.” Okay, it’s dopey language, but an appealing idea.

Is there actually a line that runs from Hollywood, the winner of the Westminster Kennel Club 2021 Toy Dog Group in 2021, all the way back to a dog in 330 BCE when Aristotle was alive? James Gorman, a journalist at The New York Times, asked dog geneticists this question for a 2021 article. The answer was no. No DNA links Aristotle’s pup and Hollywood. Elaine Ostrander, who has studied the dog genome extensively, emphasizes that “the concept of a breed did not exist” then. (I’ll address what our concept of a breed is in a bit.) The Greeks and Romans had little white dogs.

The AKC makes a similar grand claim about the pug’s lineage: “Once the mischievous companion of Chinese emperors, and later the mascot of Holland’s royal House of Orange…” In the 16th century, a distinct type of dog called a Lo-Sze was brought to Holland by the Dutch East India Company. It reportedly originated in China as a companion dog and was popular in the court of the Song dynasty (960-1279). It became popular in the Dutch and British courts; in fact, it became popular all over Europe. So far so good for the AKC description.

This dog was short legged, short mouthed, and short haired. In paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries, however, the dog is leaner all around than our current pug; it has longer legs, a thinner neck, a smaller head, fewer wrinkles, and a short but distinct muzzle. It's adorable, but doesn’t conform to the current breed standards for the pug.

"The Painter and His Pug," 1745, William Hogarth.

Imperial forces, such as the Romans, often brought their dogs, and their dogs’ genes, with them to remote outposts. Later, as in the case of the Lo-Sze in the 16th century, global trade carried new types of dogs to new places. Even when travel was arduous and slow, types of dogs moved around the world. Until the middle of the 19th century, however, dog breeding remained largely local and hit-or-miss. In general the rule was “best to best.” Breeding tended to address a “breeder’s particular need,” as Horowitz puts it, and might involve crossing similar dogs to reinforce their abilities, or different types of dogs for their complementary strengths. A dog with an especially keen nose might have been crossed with a dog with good speed and endurance. People weren’t thinking about the dog’s looks but their function. Horowitz also notes that “most puppies were the result of dogs being dogs,” so there was plenty of genetic variation.

Then breeding practices changed—not on a dime, but swiftly—as the purebred dog became a commodity in the world of fashion.

The Victorians invented the “breed” as we now know it, as dog shows and purebred dogs became wildly popular. In Pit Bull, Bronwen Dickey notes that “Roughly 75 percent of the more than four hundred dog breeds we recognize today are whimsical confections whipped up in the late nineteenth century.” Breeders chose a handful of specimens of particular types—sometimes mixing and matching, sometimes keeping true to a traditional type of dog—and then bred puppies from that limited set of individuals. They set the breed standards used to judge the dogs at shows and to determine commercial value and kept careful records of parentage in stud books overseen by national kennel clubs. This is what we mean by breed now.

Breeders focused intently on what the dogs looked like—the perfect-looking Cocker Spaniel or Gordon Setter—and paid little or no attention to function and health. At the same time, many breeders set out to create more distinctive-looking dogs to attract attention to their “products” and one-up their competitors. The breed standards, strict as they were, paradoxically allowed for exaggerations over time. For example, as Horowitz traces in one story, the Great Dane has grown bigger; in 1889 the AKC standard for the male was 120 pounds, and now it’s 140-175 pounds—putting strain on its joints and heart. The only Great Dane I’ve known died young from a heart attack.

A pug in 1915

The pug also began to morph. During the Second Opium War (1857-59), a new type of dog that resembled the pug, called a happa dog, was seized as loot from China and brought back to Europe. Stockier and with flatter faces, happa dogs, now extinct, were crossed with pugs. By the time the pug breed was accepted by The Kennel Club, the UK’s slightly older version of the American Kennel Club, as a breed in 1883, pugs had begun their transformation. They became stockier; their necks thickened (some look like tiny linebackers); their faces added more pronounced wrinkles; and their colors became more uniform. In the 1910s and 1920s, their muzzles got still shorter, their heads rounder, and their eyes more prominent. Today, some have grossly exaggerated features, what some people (I include myself) might no longer call cute but cute-ugly.

By definition a pure-bred dog is an in-bred dog. This originates with the genetic bottleneck created by selecting a small number of dogs as foundations for a breed. Pedigree breeding then closes the gene pool, as dogs only mate with other dogs whose parentage is known, can be traced to the first dogs in the breed, and meet the breed standards for size, coloring, and shape. Dogs, once bred for the work they could do, were chosen and bred instead for their looks: because they were a certain height and length; because they were pure black or spotted; because their ears were floppy or pointed. The official breed standards, which define the ideal dog and are used in dog shows, are both comprehensive and specific. The golden retriever’s AKC standards fill two pages. The size allowed, for example, has little room for variation: “Males 23 to 24 inches in height at withers; females 21½ to 22½ inches. Dogs up to one inch above or below standard size should be proportionately penalized. Deviation in height of more than one inch from the standard shall disqualify.” No wonder golden retrievers look so much alike.

Golden Reunion, Scotland, July, 2023. Roddy Mackay for "The New York Times"

The point of modern breeding practices is to create consistency, which means eliminating genetic variation. In the process of breeding dogs this way, which limits the partners, negative consequences can compound over time. It’s straight-up Mendelian genetics. Within a limited population, a recessive mutation in one dog is more likely to line up with a similar recessive mutation in another dog, so that the recessive gene will be expressed in the puppies. In Dog Sense, John Bradshaw traces the long-term effects of pedigree breeding practices:

The genetic isolation of each breed has brought about a dramatic change in the dog’s gene pool, massively reducing the amount of variation in each breed. The less the variation, the more likely it is that damaging mutations will affect the welfare of individual dogs: In order for a potentially detrimental mutation to actually cause harm, it generally has to have been present in both parents—and this is likely to occur only if the parents themselves are closely related. In some dog breeds today it is difficult to find two parents who are not closely related.

In Gordon setters a particular recessive mutation can cause Progressive Retinal Atrophy, which leads to vision loss and blindness in older dogs. There’s no treatment. As many as 50% of the setters carry this gene. Breeders can test for the gene and make sure only to cross a dog that carries the mutation with a dog that does not, but still half of their puppies are likely to carry the gene.

The American Kennel Club knows there’s trouble. Its website features a health tab for every breed. The pug’s page reads, in part:

The pug’s dark, appealing eyes are one of his main attractions, but also one of his vulnerable spots. Eye problems including corneal ulcers and dry eye have been known to occur. Like all flat-faced breeds, Pugs sometimes experience breathing problems and do poorly in sunny, hot, or humid weather.

The carefully innocuous language they use here downplays the severity of the problems pugs face and verges on being disingenuous. Below this description, there’s a list of four recommended health tests: a veterinary ophthalmologist’s eye exam, evaluations of the knees and hips, and a DNA test for Pug Dog Encephalitis (PDE). Caused by a recessive mutation, PDE inflames the dog’s nervous system and causes seizures, depression, circling, and visual impairment—and occurs in 1% of pugs. The people who run the AKC care about the health of dogs, but they’re primarily promoters. The AKC Marketplace, “your puppy search partner,” provides links to breeders all over the country.

The AKC’s Canine Health Foundation and breed clubs have teamed up with the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) to support research and share information on the health issues faced by purebred dogs. Together, the breed clubs and OFA have created health screening requirements and recommendations for specific breeds, a certification process for breeders through the Canine Health Information Center (CHIC) Program, and a publicly available database to share the outcomes. As OFA states: “A dog achieves CHIC Certification if it has been screened for every disease recommended by the parent club for that breed and those results are publicly available in the database.” This is good for dogs, breeders, and buyers.

The list of screenings for pugs on the OFA website is daunting. The CHIC program requires only three screenings—of the knees (they’re prone to dislocate) and the eyes and the genetic test for PDE, requirements set by the Pug Dog Club—but it also recommends seven more: x-rays of the hips and elbows; a genetic test for Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency, a metabolic disorder caused by recessive genes that kills red blood cells and limits the supply of oxygen to the body; a serum bile acid test for puppies to assess liver function; an x-ray of the spine; an x-ray of the trachea, which may not develop completely; and a cardiac evaluation. (Little related to BOAS appears on this list.) That’s ten screenings in total, while the typical number of screenings recommended by the CHIC program for other breeds seems to be around four. The pug is a vulnerable dog. As the 2016 UK study concluded: the pug is no longer “a typical dog from a health perspective.”

In no way do I want to downplay the vulnerabilities of other breeds. The pug may have reached a tipping point, but other breeds are also in trouble. Eye, hip, elbow, and heart screenings are common. Many recessive mutations give rise to disorders that range from annoying to fatal. Alaskan Malamutes are vulnerable to two—polyneuropathy and autoimmune thyroiditis, what we also call Hashimoto’s disease in people. Basenjis are also vulnerable to two—Progressive Retinal Atrophy, which causes night blindness, and Fanconi syndrome, which is a form of kidney dysfunction that interferes with the absorption of electrolytes and nutrients and can lead to kidney failure and death. As many as 10-30% of the Basenjis in North America may develop Fanconi syndrome, according to an article from VCA Animal Hospitals, the national veterinary chain. Reading through the CHIC program’s screening requirements is disheartening. What are we doing to our dogs?

We’ve known about the risks and damage of inbreeding for many decades. The AKC, OFA, breed clubs, and many breeders have made efforts to mitigate the worst effects with some success, but breeding is still inbreeding by its nature. We also keep accentuating breed features—the sloped back of the German shepherd, the size and weight of the Great Dane, the shortened muzzle and facial wrinkles of the pug, the size of the English bulldog’s head (most can only give birth by C-section)—that cause dogs to suffer. In a recent article in The New York Times, “This Quiz Will Change the Way You Think About Dogs,” Alexandra Horowitz argues that all purebred dogs have reached a crisis and advocates outcrossing, “the introduction of different genetic material,” for all breeds. Pugs are the bellwethers of a broad problem.

A 2021 study underscores Horowitz’s sense of urgency The research determined that the average rate of inbreeding in dogs is now at a coefficient of 0.249. That’s just under 0.250, the level for full siblings. As the authors observe, “the majority of dog breeds displayed high levels of inbreeding well above what would be considered safe for either humans or wild animal populations.” Considered safe? That’s a startling fact. They then compiled morbidity data—data about illness based on specific visits to the vet for an illness rather than, say, for a distemper shot—from a large Swedish pet insurance company and aligned that data with breeds and their levels of inbreeding. The results show clearly that the more inbred the breed, the more veterinary care those dogs need during their lives. Not surprisingly, they report “a significant difference in morbidity between brachycephalic breeds and non-brachycephalic breeds.” They also found that larger breeds, such as Great Danes, suffer more health problems.

Following the major 2016 study of pugs, the British Veterinary Association (BVA) made forceful moves. They “strongly” recommended that people not buy pugs unless breed standards changed, and partnered with The Kennel Club to educate the public, to systematically screen breeding dogs’ health, and to begin to revise breed standards. The BVA also sought to combat the pug’s popularity and lobbied greeting card companies, for example, to stop using cute images of pugs (at least one company agreed). The Kennel Club has dedicated a section of their website to the health of brachycephalic dogs, with informational videos and links to many of the veterinary studies I’ve used here. As a result of the BVA’s focused campaign—and the active cooperation of the Kennel Club—fewer people are buying pugs in the UK. Statista.com, a global data and business statistics platform, reports that after reaching a high point in 2017 pug registrations in the UK have steadily declined and in 2022 registrations were about two thirds off the peak (though it’s worth noting that, with the ongoing poor economy in the UK, dog ownership is down overall).

A pug from the 19th century

Does this mean the end of the pug? There’s probably no way the breed survives in its current form. If breed standards don’t shift, pugs face more illness and suffering, and what’s already bad will get worse. If breed standards change enough to address BOAS, other health issues created by their body shape, and recessive genetic disorders, the pug will definitely look different. Its flat face will be one of the first things to go.

But will the pug really disappear? Some breeders have started to outcross, breeding pugs with Jack Russell or Parson Russell terriers to create what they’ve dubbed the Retro Pug. Pug Dog Passion, a Swedish website run by two people who really love pugs, proposes new breed standards that directly address the pug’s health concerns and include regular outcrossing to maintain genetic diversity in the long run. A one-and-done approach to outcrossing won’t work, since “different genetic material” needs to be introduced regularly. A 2018 study recommends an outcrossing rate of about 5% of new litters across 25 years to keep inbreeding to a safely low level. The dogs that meet these new standards resemble the pugs of the 18th and 19th centuries, the small short-mouthed dogs that became so popular when they were first brought to Europe, before the Victorian purebred craze took hold. Retro is right.

A retro pug with a longer neck and a snout

For 150-plus years breeders have shaped the pug to conform to human tastes. We have made its body blockier, its neck shorter, its face flatter, its tail curlier, its head bigger, its pelvis narrower—and as a result many of them can barely breathe or walk. Though we love pugs, we’ve put their welfare at risk. The pug may no longer be genetically viable. In fact, the larger project of pedigree breeding—which roughly dates to the founding of The Kennel Club in England, in 1873—has created many breeds that may no longer be viable.

The domestic dog is the most varied species on the planet—from the flat-faced pug to the pointy-nosed whippet, the low-rider Bassett hound to the towering Irish wolfhound, the six-pound teacup Chihuahua to the 230-pound mastiff, the spotted Dalmatian to the black-coated Labrador. The variety of breeds is astonishing and appealing. But we need to back up. Despite what Mae West said, too much a good thing may not be wonderful, at least not for the dogs.

Dog breeds have never been static. Old photographs and paintings of pugs make that clear. It’s easy to think that the pug is the pug that trots down the sidewalk in 2024, but it’s only the 2024 version. Pugs were pugs in 1974, in 1924, and in 1885, when they were first recognized by the AKC, and people loved them all. We need to help pugs continue to evolve, but this time with an emphasis on their health and genetic diversity as well as their cute looks. If we change breeding practices and start systematically outcrossing, we’ll lose the extreme qualities of many breeds, but we’ll gain something more important: healthier, happier, and longer-lived dogs.

Even well-meaning and responsible breeders, who follow the health protocols, cannot thwart the laws of genetics or alter the anatomical fact that dogs have muzzles not flat faces. So go ahead and adopt an older pug who needs a home, but if you really can’t resist buying a pug puppy, buy a retro pug. They’re great dogs!

The once and future pug!

References (in the order of their first appearance):

John Bradshaw. The Animals Among Us: How Pets Make Us Human. Basic Books, 2017.

Bridget M. Waller, et al. “Paedomorphic Facial Expressions Give Dogs a Selective Advantage.” Plos ONE, December 26, 2013.

Del Richards. “What Is a Pug?” Pug Dog Club of America. “About the Pug,” June, 2013.

Dan G. O’Neill, et al. “Demography and Health of Pugs Under Primary Veterinary Care in England.” Canine Genetics and Epidemiology 3, #5 (June 10, 2016.)

Dan G. O’Neill, et al. “Health of Pug Dogs in the UK: Disorder Predispositions and Protections.” Canine Medicine and Genetics 9, #4 (May 18, 2022).

Royal Veterinary College. “New Research Shows Pugs Have High Health Risks and Can No Longer Be Considered a ‘Typical Dog’ from a Health Perspective.” VetCompass News, May 18, 2022.

Robert Hubrecht, et al. “The Welfare of Dogs in Human Care.” The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People, 2nd ed. James Serpell, ed. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

John Bradshaw. Dog Sense. Basic Books, 2011.

Alexandra Horowitz. Our Dogs, Ourselves: The Story of a Singular Bond. Scribner, 2020.

Rowena Packer, et al. “Impact of Facial Conformation on Canine Health: Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome.” PLoS ONE 10, 2015.

Rowena Packer. “Spinal Problems in Brachycephalic Dogs.” The Kennel Club.

Anonymous. “Pugs Are Anatomical Disasters. Vets Must Speak Out—Even If It’s Bad for Business.” The Guardian, September 22, 2016.

James Gorman. “How Old Is the Maltese, Really?” The New York Times, October 10, 2021.

Bronwen Dickey. Pit Bull: The Battle Over an American Icon. Penguin Random House, 2016.

Krista Williams and Robin Downing. “Fanconi Syndrome in Dogs.” VCA Animal Hospitals.

Alexandra Horowitz. “This Quiz Will Change the Way You Think About Dogs.” The New York Times, May 9, 2024.

Danika Bannasch, et al. “The Effect of Inbreeding, Body Size and Morphology on Health in Dog Breeds.” Canine Medicine and Genetics 8, #12 (December 2, 2021).

The Kennel Club. “Tackling Health and Welfare Issues in Brachycephalic Dogs.”

Therese Rodin and Mats Rundkvist. “A Healthy Pug Standard.” Pug Dog Passion. The photos of retro pugs come from this site.

J.J. Windig and H.P. Doekes. “Limits to Genetic Rescue by Outcross in Pedigree Dogs.” Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics 135, #3 (June, 2018).

Requirements and recommendations for health and genetic testing