Take a Walk. Take the Dog.

One of the great days for a walk!

There are the days when storms are predicted. On this particular June day, the rain had just started when I headed out, but I figured I could sneak in a walk before the real storm rolled in. Wrong. Within a couple of minutes, light rain turned into a torrent. Water swirled around my ankles. Bear, his thick black fur plastered to his body, stopped dead in his tracks and gave me the canine version of a WTF look. We hightailed it for shelter.

Then, there are the January mornings when it’s so cold that tiny icicles form on your eyelashes. No way I’d be out there if it weren’t for the dog. But I’m not alone out there. Like mail carriers, the core crew of early morning dog walkers is making their appointed rounds. And I have to admit, a clear January dawn is pretty spectacular.

Extremes aside, what really matters is the sum of days—balmy, cool, drizzly, brilliant, whatever the day dishes out—when you walk the dog before work, after work, and on weekends. Two recent studies about physical activity, published in the spring of 2019 and both reported in the New York Times, point to why it’s healthy to keep a dog. And why, as we get older, we should keep on keeping dogs.

Bennie, a favorite of the neighborhood.

The first study, published in Nature: Scientific Reports in April, was conducted in Cheshire in northwest England. These researchers, led by Carri Westgarth, a Lecturer in Human-Animal Interaction at the University of Liverpool Department of Epidemiology and Population Health, tested the assumption that owning a dog translates into more physical activity. Though this seems like a no-brainer, it hadn’t been corroborated in a rigorous way. Earlier findings had been promising, but past studies had been small and heavily reliant on personal reports, which aren’t that accurate.

They designed a larger more objective study using the international guideline that adults should get 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week (this includes walking). They compared and contrasted the activity levels of a large group of dog owners and non-dog owners, including 646 adults and 46 children in 385 households across two months, using objective measures in addition to self-reports. They included all members of the households, including children. Further, the subjects all lived in the same community and had similar access to places to walk. Finally, the study accounted for other kinds of physical activity as well.

Correlation is not causation, of course. People who choose to get dogs may be more active to start with. Conversely, having a dog cannot magically make a person walk. In fact, a small subset, 10%, of the dog owners in this study didn’t walk their dogs at all (sounds like a set-up for some unhappy dogs) and were less physically active than both dog owners and non-dog owners alike.

The findings provide strong evidence that owning a dog promotes healthy activity. 64% of the dog owners in the UK study walked their dogs at least 150 minutes per week; others clocked in at about 300 minutes per week. The dog owners were four times more likely to meet physical activity guidelines than the non-dog owners. What’s more, walking the dog did not replace other physical activity, but supplemented it. The children of dog owners were more active (though the sample of children was small). And the walks people took were more frequent rather than longer, which is also healthy because it breaks up our periods of inactivity.

These researchers conclude that “our pet dogs play an important role in keeping us healthy.” This makes dog walking not just a private matter but a public health and policy concern—because, with so many dogs living in so many homes, “even small effect sizes might contribute considerable additional physical activity at the population level provided, of course, that the dogs are actually walked.”

The second study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association: Internal Medicine in May, comes out of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Like the other study, it tested an assumption, this one about physical activity. Researchers, led by I-Min Lee, a principal investigator for the Women’s Health Study, wondered: If older women take more steps each day, are their mortality rates lower? How many steps make a difference? The study concerned overall mortality rates, with no focus on particular medical conditions, and tracked both the number of steps taken and the intensity of the exercise. Some of the results surprised no one, but others did.

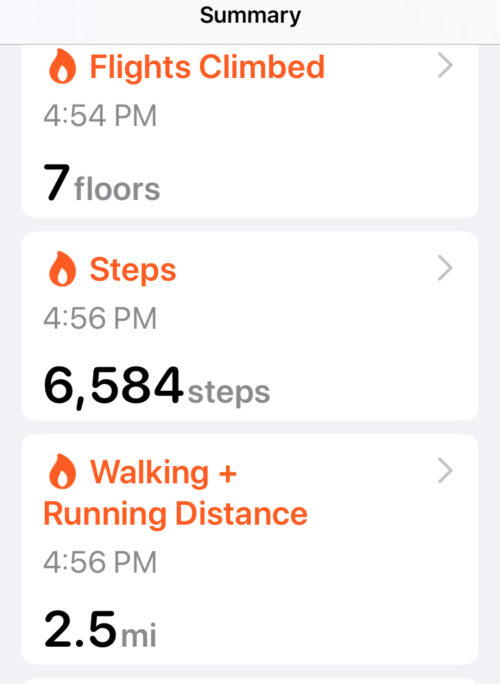

A bit of background first. The guideline of 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week, which was used in the Cheshire study, can be hard to track in real life. Consequently, many people, from doctors to trainers to app designers, have started to use a more concrete metric: steps per day. With our phones and fit-bits, we can now measure our activity. 10,000 steps per day has become the gold standard.

Ten thousand’s a nice round number. It’s high—and challenges most of us to exercise more. But where did this number come from? As Gretchen Reynolds reports in her coverage of this study, it emerged, as many numbers do, by chance when, in the 1960s, a Japanese company introduced a pedometer named “10,000 Steps.” The name morphed into a “fact.”

Dr. Lee wanted numbers based in research. Through the Women’s Health Study, she had access to an extraordinary range of information. In 1993 nearly 40,000 women, all working in health professions, volunteered for a 10-year randomized trial. At that time, participants were 45 and older and in good health. After the trial was over, the women volunteered to continue. They now provide annual updates on their health through surveys, medical records, and some additional studies, including specific measures of physical activity.

Using this database, Lee’s team correlated steps per day, the intensity level of physical activity, and mortality rates across about 4.5 years in nearly 17,000 women with a mean age of 72. The primary outcome was what you’d expect: Mortality rates decreased with more steps per day.

What surprised the team was that it didn’t take many steps to make a significant difference. Among this group of older women, the study concludes, “approximately 4400 steps per day was significantly related to lower mortality rates compared with approximately 2700 steps per day.” Mortality rates kept going down as steps per day went up but leveled off around 7500, and after accounting for the total steps per day, the intensity level didn’t make much difference. As Reynolds puts it, “the sweet spot for reducing risk of premature death” is about 4400 steps per day. The difference between 2700 and 4400 steps is startling: those women who took 4400 steps were 40% less likely to have died 4.5 years later.

There are caveats. Women who were already ill may have walked less. Or you could put it the other way around: the women who were healthier were more likely to walk more. Further, this study only focuses on older women and overall mortality rates. It does not take any particular diseases or medical conditions into account. There are limits to its applications.

Nevertheless, there’s a clear takeaway for women (I bet it applies to men, too) as they get older: Take more steps per day. You don’t have to walk for miles and miles, and you don’t have to run. Take another walk. The dog will be glad to provide that extra incentive—nudges, dramatic sighs, longing looks, whatever it takes—to get you out the door, no matter the weather.

References (in the order of their first appearance):

Thanks to Gretchen Reynolds of the New York Times for her excellent reporting on exercise and health.

Gretchen Reynolds. “Dog Owners Get More Exercise.” New York Times, May 29, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/29/well/move/dog-owners-get-more-exercise.html?searchResultPosition=20

Carri Westgarth, Robert M. Christley, Christopher Jewell, et al. “Dog Owners Are More Likely

to Meet Physical Activity Guidelines Than People without a Dog: An Investigation of the Association between Dog Ownership and Physical Activity Levels in a UK Community.” Scientific Reports 9, April 18, 2019.

I-Min Lee, Eric J. Shiroma, Masamitsu Kamada, et al. “Association of Step Volume and Intensity with All-Cause Mortality in Older Women.” Journal of the American Medical Association: Internal Medicine, May 29, 2019 (179:8), 1105-1112.

Gretchen Reynolds. “Even One Extra Walk a Day May Make a Big Difference.” New York Times, June 5, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/05/well/move/even-one-extra-walk-a-day-may-make-a-big-difference.html?searchResultPosition=18