Horsepower: Rereading “Black Beauty”

An Orlov Trotter that looks a bit like Black Beauty

I wasn’t crazy for horses like some girls, though in fourth grade my best friend and I made regular trips to Woolworths and collected a small herd of plastic ones. I was crazy, however, for books about horses, novels like The Black Stallion, My Friend Flicka, and their sequels. I loved the stories because of the bond that grows between the kid and the horse. But they’re really human stories—with horses in them.

Black Beauty is different, because it’s a horse story—with humans in it. Anna Sewell gives us “the life of a horse” and narrates things entirely from Black Beauty’s point of view. As a colt, Beauty hears and sees a train for the first time: “with a rush and a clatter, and a puffing out of smoke—a long black train of something flew by, and was gone almost before I could draw my breath.” He runs madly around the pasture trying to get away. I realized for the first time that animals experience things really differently. At nine, I hadn’t yet grasped this fact, though it instantly made sense, and I never thought of animals in quite the same way afterwards. I loved the book.

Black Beauty was full of surprises when I read it as a kid. As I reread it many years later, the book made me think about—and want to know more about—the early animal welfare movement, class and poverty in Victorian England, the role of the horse in the 19th century, and Sewell’s life. There were more surprises to come.

It turns out that Black Beauty wasn’t written for kids at all. The beloved book of my childhood, and many other people’s childhoods, was a major social-protest novel that helped popularize the animal welfare movement. Published in Britain in 1877, it became one of the most successful books of the 19th century and is described in the 1998 Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare as “the most influential anti-cruelty novel of all time.”

In the late 18th century, the philosopher Jeremy Bentham revisited the ancient issue of the ethical treatment of animals. Would we include non-human animals in our moral consideration, on what grounds, and to what effect? He concluded: “the question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?” His approach altered the debate about animal welfare, and the first protective laws to reduce suffering, mostly for livestock, passed in Europe in the 1820s. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the very first animal welfare organization in the world, was founded in Great Britain in 1824. The organization received the young Queen Victoria’s blessing and became the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) in 1840.

In the late 18th century, the philosopher Jeremy Bentham revisited the ancient issue of the ethical treatment of animals. Would we include non-human animals in our moral consideration, on what grounds, and to what effect? He concluded: “the question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?” His approach altered the debate about animal welfare, and the first protective laws to reduce suffering, mostly for livestock, passed in Europe in the 1820s. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the very first animal welfare organization in the world, was founded in Great Britain in 1824. The organization received the young Queen Victoria’s blessing and became the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) in 1840.

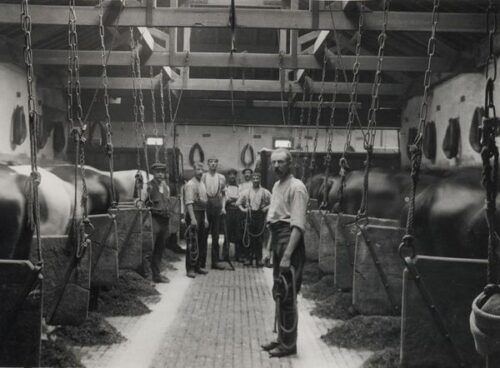

Anna Sewell answered Bentham’s question emphatically: Horses suffer. While she hoped that those who owned horses would pay attention to her book, she wrote primarily for the men and boys who worked in the stables and drove horses. These readers weren’t abstractions to her, but were the men and boys whom she had taught in Sunday school and adult literacy classes throughout her adult life. Her original title was Black Beauty: His Grooms and Companions. The Autobiography of a Horse. The heroes of the book—along with Black Beauty and the other horses and ponies—are knowledgeable and kind grooms, drivers, riders, cabmen, stable hands, and farmers. Sewell honors their labor and the powerful horse-human partnership that their knowledge makes possible. Beauty observes an old man who delivers coal: “He and his old horse used to plod together along the street, like two good partners who understood each other; the horse would stop of his own accord, at the doors where they took coal off him; he used to keep one ear bent towards his master.” Unfortunately, though, the humans in the story are often villains. If you look around, Sewell tells us, you’ll see horses overworked, mistreated, and dying. It could be different.

The novel is part exposé and part horse-care manual from a horse’s point of view. Sewell wanted her readers not only to appreciate that horses suffer but to understand what causes their suffering and how their needs can be met. She sought to “induce kindness, sympathy, and an understanding treatment of horses.” The book can feel preachy (I didn’t notice this when I was a kid), but the fact that a horse is giving us the low-down makes the lessons more palatable. Many of those lessons are straightforward and practical.

Black Beauty became a kid’s book because it’s compelling. Sewell knew that a sympathetic hero and a good story would carry the reader through, so she wrapped up the didactic bits in action, kept the chapters short and focused, and wrote clean, clear prose. It’s still highly readable in 2024. She includes emergency late-night rides, a fire in the stable, long wet days pulling a cab through London streets, horse fairs when Beauty’s future is on the line, and the death of his “fast friend” Ginger from over-work.

In his early years, Beauty has the best life a horse in his place and time could have. After he moves from his first home to a small estate nearby, he shares a stable with three other horses (including Ginger) and a pony, and “all who had to do with me were good, and I had a light and airy stable and the best food.” Cruelty and mistreatment are only scary stories that the other horses tell him.

Then Beauty’s life takes a harsh turn. Kind masters and grooms give way to ignorant, negligent, callous, and cruel ones. The scary stories become reality. He is sold and sold yet again; and each time he is sold, he becomes more worn out, “worth” less, and more vulnerable.

He wins a three-year reprieve with a kind London cab driver, Jerry, who takes excellent care of Beauty and his other horse, Captain. Beauty must work hard but knows that “for a cab horse I was very well off indeed.” Beauty pities the plight of other horses, especially those hauling freight and working for the big cab companies. Sadly, Jerry is nearly as overworked and vulnerable as Beauty is. When he gets sick and can no longer drive his cab, Beauty’s life takes another bad turn.

Beauty is sold as a cart horse to a wheat dealer, and then to the dreaded cab company. Constantly overloaded and overworked, he suffers like the horses he had pitied before. His health deteriorates, and his spirit begins to break. In the story’s climactic scene, he collapses and nearly dies, but luck brings him full circle to a safe, secure place back in the country. “I have nothing to fear; and here my story ends. My troubles are all over, and I am at home.” I still feel the relief and pleasure of that happy ending. As a kid, I would have been so torn up if Beauty had died.

Black Beauty takes the reader on a tour of Victorian England as seen from the stable—a kind of Downton Abbey for horses. It’s also a tour of the humans who control Beauty, since he’s entirely at their mercy. He always reports on the character of his owners, grooms, and drivers; the work he does; and the quality of his stable and food. Historian Ann Norton Greene notes that “Beauty’s life becomes a descent through the equine class system, from fashionable London carriage horse to livery horse, cab horse, and cart horse.” Sewell makes it crystal clear, however, that no class of humans is better or worse to horses than any other. The horse’s-eye view of humans, with heroic exceptions like Jerry, is pretty grim. Sewell forgives ignorance—grooms and drivers can learn; that’s one hope of the book—but never cruelty or negligence.

Late in the novel when Beauty has become a cart horse, but before he works for the big cab company, he is struggling to haul a load up a steep hill. When the carter keeps whipping him, a lady asks the man to stop “in a sweet, earnest voice” and offers to help. (According to her niece, Sewell stepped in when she saw helpless people or animals treated badly, but was more likely to use “burning words” than sweet ones.) When the man laughs at her offer, she persists, “‘You see,’ she said, ‘you do not give him a fair chance; he cannot use all his power with his head held back as it is with the bearing rein; if you would take it off, I am sure he would do better—do try it,’ she said persuasively.” Throughout the book, Sewell targets the bearing rein. It forced the horse’s head into an unnaturally high and tight position, restricted its breathing, caused pain and long-term damage, and limited a horse’s ability to lower its head to pull loads. What’s sadder, the rein was fashionable, especially among the wealthy, not for any practical reason but only for the look it created: it made the horse hold its head up and froth at the mouth. Beauty comments, “Some people think it very fine to see this, and say, ‘What fine, spirited creatures!’” But, he adds, “it is just as unnatural for horses as for men to foam at the mouth.”

Late in the novel when Beauty has become a cart horse, but before he works for the big cab company, he is struggling to haul a load up a steep hill. When the carter keeps whipping him, a lady asks the man to stop “in a sweet, earnest voice” and offers to help. (According to her niece, Sewell stepped in when she saw helpless people or animals treated badly, but was more likely to use “burning words” than sweet ones.) When the man laughs at her offer, she persists, “‘You see,’ she said, ‘you do not give him a fair chance; he cannot use all his power with his head held back as it is with the bearing rein; if you would take it off, I am sure he would do better—do try it,’ she said persuasively.” Throughout the book, Sewell targets the bearing rein. It forced the horse’s head into an unnaturally high and tight position, restricted its breathing, caused pain and long-term damage, and limited a horse’s ability to lower its head to pull loads. What’s sadder, the rein was fashionable, especially among the wealthy, not for any practical reason but only for the look it created: it made the horse hold its head up and froth at the mouth. Beauty comments, “Some people think it very fine to see this, and say, ‘What fine, spirited creatures!’” But, he adds, “it is just as unnatural for horses as for men to foam at the mouth.”

When he is released from the bearing rein, Beauty lowers his head, throws his full weight into the collar, and hauls the heavy cart the rest of the way up the hill. The lady tries to persuade the man to leave the rein off for good. He resists because he fears becoming “the laughing-stock of all the carters.” Once the lady leaves, however, the man partly comes around, as Beauty observes: “I must do him the justice to say that he let my rein out several holes, and going uphill after that he always gave me my head.” People can learn.

Another hero of this story is Anna Sewell herself. The more I learned, the more I admired her. For one thing, she must have been tenacious. Black Beauty, her first and only novel, was written across a span of six years as she grew sicker and weaker. At times, she was too weak physically to write–but she kept composing in her head anyway. She could so easily have lost confidence and given up.

Further, she was an independent and creative thinker. The novel was original in at least three ways. First, she flouted gender norms by writing about horses, which were the domain of men. Second, she flouted class norms by writing the book for those who worked with horses, rather than for those who owned them. Horse-care manuals at the time targeted owners, especially hunters. Third, she treated Beauty with honor and respect and created an autobiographical portrait befitting a person.

Today, the novel no longer seems that original. We no longer feel how bold it was to go against gender and class norms the way she did. Moreover, we take this fictional perspective for granted—that an animal has a distinct story—but that’s in part because of this book.

Anna Sewell’s life (1820-1878) gave me a sobering sense of how financially precarious even middle-class people’s lives were in England in the 19th century. Like Beauty, her family descended through the class system. Anna’s mother, Mary, had grown up on a thriving family farm in the English county of Norfolk and attended school. They were landowners in a small town and relatively secure. During the economic upheavals created by the Napoleonic Wars of 1800 to 1815, however, her father was forced to sell the farm. As a result, Mary had to go to work as a teacher until she married a fellow Quaker, Isaac, more out of necessity than love. But she didn’t find financial security; Isaac’s work life was unstable, the family’s income uneven and unreliable.

When Anna was really young, Isaac went bankrupt. Mary couldn’t afford books for her children, Anna and her younger brother, Philip, so she wrote her own primers, sold them to a publisher, and used the money she earned to buy books. Anna didn’t go to school until she was 12 because they couldn’t afford the school fees (Philip started earlier, when he was nine), but Mary taught her children thoughtfully and well.

The family moved frequently as Isaac changed jobs. Though Anna experienced periods of stability and comfort, she learned early that life could change radically. This was especially true for her physically. As a child, she was bold and independent; but when she was about 12, she fell, badly twisted both ankles, and had to rely on crutches afterward. Then, at 19, she developed chronic fatigue, pain in her muscles and joints, tenderness in her lymph nodes, and headaches. Anna lived with limited mobility and the ups and downs of an mysterious chronic disease for the rest of her life. She remained single and dependent on her family.

How did an original novel come out of this unsettled and seemingly pinched life? And how did Anna Sewell learn so much about horses?

When Anna and Philip were young, Isaac and Mary were working so hard that they sent the children to spend time with relatives who still owned and worked a farm. There, Anna learned to ride (sidesaddle) and to drive a carriage. After she injured her ankles, she returned to the farm to recuperate and again rode frequently. During one period years later, Anna drove her father each day to and from the train station in a light one-horse carriage. For about six years the family lived on an isolated farm and Anna rode out on her own, with her horse essentially serving as her chaperone. Riding gave her, a single woman whose walking was limited, freedom of movement and a chance to get exercise. Her biographer Adrienne Gavin believes that riding always gave Anna “a sense of power and independence.” At times, however, the family couldn’t keep a horse at all.

Anna Sewell

When it came to writing, Anna had a creative model in her mother. In the 1850s, Mary returned to writing and published a number of books of verse for children, and Anna served as her editor. One, Mother’s Last Words (1865), sold over a million copies in the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States. Her books’ success earned her some fame and the family a bit of financial cushion.

Anna began to work on Black Beauty when she was in her early 50s, at the same time that her illness forced her to give her pony away. She remained housebound for the rest of her life. Was writing the book a way to keep engaging with the world? To express her gratitude to horses? Both, I’d guess.

Her brother and her mother wholeheartedly supported her project. Anna spent a lot of time talking with Philip about horses in general and about his horse Bessie, possibly the model for Black Beauty, in particular. Both Philip and Mary read and commented on drafts. Mary made fair copies and took dictation when Anna was too weak to write. In 1877, Anna completed the manuscript. Her mother took it to her own publisher, who bought it for £40, the equivalent of $5,700 in 2024.

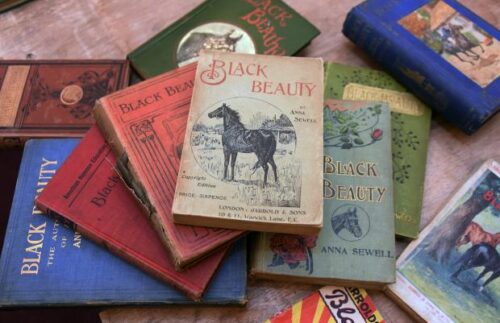

A first edition of "Black Beauty"

Insecure as the Sewell family was, their lives were far easier than the lives of most of their neighbors. Awareness of poverty and its profound challenges runs throughout Black Beauty. The fictional drivers and cabmen are forced to overwork themselves and their horses. The character Jerry dramatizes these pressures and their cost. Jerry collapses, possibly with pneumonia, and can no longer drive his cab. Happily, he finds a groom’s position in the countryside, but only by chance—just as chance later saves Beauty.

Everywhere they lived, Mary and Anna served others. Anna was a teacher, a social activist, and a social worker, though never in a paid position. Primarily, she taught reading and writing to children and working adults in Sunday schools and night courses. In addition, she and her mother helped out those who were poor or sick, founded a community library, created a Working Men’s Hall, campaigned for temperance, and collaborated with others to create an alternative to the local poorhouse for orphans. They formed a team, a “pair of twin souls” in the words of a family friend, who sought to make their community better. Although Anna was ill and housebound when she wrote Black Beauty, the novel emerged from an active, purposeful life.

In the 19th century, horsepower kept the industrial economy moving. While steam power drove factories, boats, and locomotives, horses did everything that cars, trucks, vans, buses, and light rail do now, and more. Horses moved people and goods; pulled ambulances, fire wagons, freight wagons of all sizes, canal boats, cabs, buses, and trolleys; and powered construction machinery such as cranes, pumps, and excavators. They linked parts of the economy together—moved raw materials to and from boats and freight trains, food and manufactured goods to market and then to people’s homes. As the economy grew and more goods were produced, more and more horses were needed.

Their numbers peaked at the end of the 19th century. In Great Britain, at the time of the 1901 census, there were an estimated 3.25 million horses in a country with 41 million people. About half worked in farming and the other half in transportation, shipping, and mining, according to the National Archives. Horses moved more goods by weight than trains did. Across the country, over a million horses were used for transporting goods and people, with the greatest concentration, an astronomical 300,000, in London, with its population of 6.5 million people. (By contrast, in 1900 the much larger United States had many more horses. There were approximately 21.5 million horses–including ponies, mules, and donkeys–and 76.3 million people, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.)

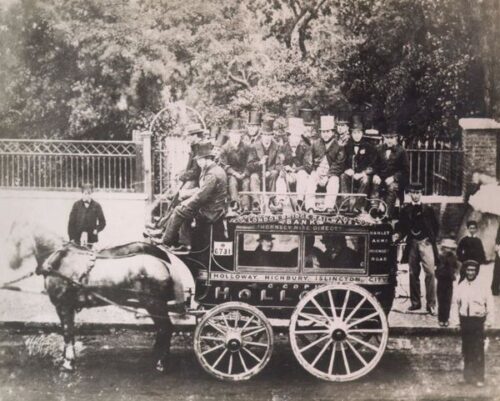

London street scene

The next time you’re stuck in traffic, imagine that every car, van, bus, and truck is pulled by horses, singly or in teams. Take away most of the rules. Take away the smooth road surfaces, and replace them with cobbles, dirt, or mud. Take away stop signs and traffic lights. There were some right-of-way conventions and some one-way streets, but not much else.

Beauty describes a street that he and Jerry must navigate as they rush to make a train:

I had a very good mouth—that is, I could be guided by the slightest touch of the rein, and that is a great thing in London, amongst carriages, omnibuses, carts, vans, trucks, cabs, and great waggons creeping along at a walking pace; some going one way, some another, some going slowly, others wanting to pass them, omnibuses stopping short every few minutes to take up a passenger, obliging the horse that is coming up behind to pull up too, or to pass, and get before them, but just then something else comes dashing in through the narrow opening, and you have to keep in behind the omnibus again; presently you think you see a chance, and manage to get to the front, going so near the wheels on each side that half an inch nearer and they would scrape.

Increasingly during the 19th century, horses pulled not only single cabs such as Jerry’s but also buses and trams, and were owned by large corporations. The first horse bus in London, which began to operate in 1829, launched a revolution in public transportation.

A London horse bus, with more people on top than inside

Within three years, 400 horse buses were running. Within 25, the London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) bought out three quarters of London’s horse buses and, by 1860, was carrying 40 million passengers a year. Horse tramlines were added in parts of the city, and since the trams rolled more easily on tracks, it became possible to move more people with the same number of horses. In the 1860s, London began to build and operate the Underground to ease the congestion in the streets, but buses, trams, and cabs were still needed where the lines didn’t reach. In the 1890s, some 25,000 horses were hauling 2000 horse buses.

The immense demand for horsepower created thousands and thousands of jobs–for stable hands, coachmen, cabmen, bus drivers, teamsters, smiths, farriers, saddlers, trainers, veterinarians, and horse breeders. While human knowledge about horse behavior and care had accumulated over centuries, many of the new owners and workers were ignorant and inexperienced. There was neither time nor resources for apprenticeships. Workers were also under intense and constant pressure to move more goods, pick up more passengers, drive more hours, and meet deadlines. Black Beauty chronicles the consequences for horses and drivers alike.

For a time, Beauty is owned by a company that rents out horses and carriages. Many of the drivers are inexperienced, and the worst treat him like a machine: “They always seemed to think that a horse was something like a steam-engine, only smaller. At any rate, they think that if only they pay for it, a horse is bound to go just as far, and just as fast, and with just as heavy a load as they please.”

Horses frequently collapsed or died in the streets and at work sites. Not surprisingly, animal welfare advocates zeroed in on the mistreatment of horses.

Published in late November, 1877, Black Beauty hit a nerve. It was reprinted five times in its first year and 35 times within the next ten. By 1891, about one million copies had been sold. A century later, some 40 million copies in multiple languages had been sold. And the book keeps on selling. I picked up a Puffins Classics edition from my local bookstore, with no need to special order it.

The book’s huge global success can largely be attributed to an American animal welfare activist. In the United States, the animal welfare movement came into existence right after the Civil War. In 1866, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) was founded in New York, followed in 1868 by the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (MSPCA). The ASPCA, led by Henry Bergh, actively and provocatively intervened in cruelty cases—stopping overloaded horse trolleys in the streets, breaking up dog-fighting rings—and lobbied hard for anti-cruelty laws and the power to enforce them. By contrast, the MSPCA focused on preventing cruelty through education. George Angell, the founder of the MSPCA, built a large network of community leaders, school principals, and teachers across the country. Angell and his allies sought to foster sympathy for animals by showing, according to Henry Bergh’s biographer, “how very human a beast could be.”

In 1890, Angell discovered Black Beauty with its very appealing hero, promptly pirated the book, and became its biggest champion and publicist. Sewell’s intentions to “induce kindness, sympathy, and an understanding treatment of horses” aligned perfectly with his mission. Angell raised money to print and distribute the novel to owners, stable hands, drivers, and school children throughout the United States for free or for pennies. He commissioned translations into German, Italian, Spanish, Swedish, and Japanese over the next couple of years (it had already been translated into French)—and later into Dutch, Hindustani, Greek, Chinese, Turkish, Armenian, and Braille. Between 1890 and 1910, the MSPCA and its allies gave away 2 to 3 million copies.

Sadly, Sewell died five months after her book was published. Although she didn’t witness its wide success, she lived long enough to know that it was receiving enthusiastic reviews and selling well. The RSPCA endorsed it as “one of the best books recently published in support of our principles.” Edward Fordham Flower, a leading anti-cruelty campaigner and author of the exposé Bits and Bearing Reins (1875), admired Black Beauty and hoped to meet Sewell if she ever came to London (she couldn’t, of course). Along with other readers, he marveled that a woman knew so much about horses. A friend of Sewell’s wrote to her, “One would think you had been a horse-dealer, or a groom, or a jockey all your life.” This was unthinkable in her day.

Black Beauty reached readers who would never have picked up Bits and Bearing Reins or a horse-care manual. Sewell helped millions of people see through a horse’s eyes and empathize. Each new reader encounters Beauty for the first time and realizes that a horse is not an object but a being with a life and a story–and that a horse suffers, just as we do.

Ann Lindo at the Home of Rest for Horses

For some readers, this realization led to significant action. Black Beauty inspired Ann Lindo to create what’s considered to be the first horse sanctuary and charity in the world in 1886. She founded the Home of Rest for Horses to serve the twofold purpose of helping the working cab horses of London and their driver-owners. Like Sewell, Lindo understood that the drivers had to work long hours if they hoped to support themselves and their families–and that this frequently meant overworking their horses. The Home of Rest for Horses took in a sick, exhausted horse; loaned the driver a healthy replacement, along with a supply of food, for a reasonable fee; and after the horse had rested and regained its health and strength, returned the owner’s horse. The system was ingenious–and an immediate success, as the Home of Rest for Horses attracted both users and donors. I think it’s safe to say that Anna Sewell would have loved it. Others followed Lindo’s example soon after in the United Kingdom, the United States, and elsewhere and created horse sanctuaries.

Years later, reading Black Beauty as a boy moved the writer Cleveland Amory (1917-1998) to become a life-long activist for both wild and domestic animals. In 1979 he created an animal sanctuary on 1400 acres of land in Texas and named it Black Beauty Ranch. It is now home to some 650 animals–from horses to kangaroos, pigs to zebras–that have been rescued from research labs, roadside zoos, exotic pet traders, and other dangerous situations. Amory’s New York Times obituary in 1998 noted that he believed that “if everyone thought about what it would be like to be in an animal's place, there might be more compassion in the world.”

Now, there are an estimated 200 horse sanctuaries in the United Kingdom and 600 in the United States. They range from small farms that take in a few horses, ponies, donkeys, and mules to large sophisticated operations. (My research about horse sanctuaries took me down quite a few rabbit holes. If you like rabbit holes, too, see the very end of this. There are some notes on sanctuaries, shelters, and rescues after the list of references.)

George Angell made sure that Black Beauty reached millions of readers all over the world. By putting the book in the hands of so many schoolchildren, his campaign also helped transform a social protest novel into a children’s classic. The word classic suggests that the novel also became a historical artifact. Indeed, by the time I read Black Beauty in the mid-1960s, the world of the novel was gone, though it still lingered in my grandparents’ and even my parents’ memories. The word classic also means that the book packs emotional and imaginative power. Books don’t become children’s classics unless they’re meaningful and authentic and unless children, who are demanding readers, want to read them.

Black Beauty raised public awareness, but what finally, fully transformed the lives of millions of working horses was technological innovation. In 1899, the London General Omnibus Company introduced motorized buses, and within 15 years Londoners were riding in motor vehicles rather than horse-drawn carriages and buses. That’s a swift change. Horses still hauled individual cabs and freight carts and, according to The National Archive, outnumbered tractors on British farms until 1950. But the age of the working horse in industrialized countries was at an end.

This story has sweet endnotes. In 2022, Anna Sewell’s birthplace in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, officially became the Anna Sewell House. It is now run as an education center by Redwings Horse Sanctuary, the largest horse sanctuary in the United Kingdom.

Redwings teamed up with the University of East Anglia to publish a special edition of Black Beauty, released on November 24, 2023, the anniversary date of its original publication. Half the proceeds will go to support the work of Redwings. As far as the staff at Redwings know, this is the first time that Black Beauty’s sales will directly support horse welfare. To celebrate the publication, Redwings sponsored a writing competition for young people, ages 7-12 and 13-18, to write a story from the point of view of an animal. One of the judges remarked, “We were blown away by the number of entries we received, which were staggeringly good. It was both a joy and a heartbreak to read the moving work by these young writers.” Anna Sewell’s spirit lives on.

References (in the order of their first appearance):

Adrienne E. Gavin. Dark Horse: A Life of Anna Sewell. Sutton, 2004.

This book provided me with biographical background and quotations from Sewell and her contemporaries. It also provided information about Black Beauty's composition, publishing history, reception, and success. You can also find encyclopedia entries on both Anna and Marty Sewell.

Anna Sewell. Black Beauty. 1954. Introduced by Meg Rosoff, illustrated by Charlotte Hough. Puffin Classics, 2015.

Bernard Unti. “Sewell, Ann.” Marc Bekoff and Carron A. Meaney, eds. Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare. Routledge, 1998.

Anne Norton Greene. Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America. Harvard University Press, 2008.

This book focuses on the horse in the United States starting with early colonial history and shows how our reliance on the horse shaped land use, historical development, and industrialization. It helped me understand the work of horses in the industrial economy and city. It includes a section on Black Beauty.

The National Archives, United Kingdom, “Living in 1901.”

London Transport Museum. “London’s Horse Bus Era, 1829-1910.”

Ernest Freeberg. A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement. Basic Books, 2020.

This biography of Bergh and his founding of the ASPCA included sections on George Angell, his emphasis on humane education, the work of the MSPCA, and Black Beauty.

The Horse Trust, “Our Story.”

Enid Nemy. “Cleveland Amory Dies as 81; Writer and Animal Advocate.” New York Times, Oct. 16, 1998.

“Redwings Takes on Historic Anna Sewell House” (July 21, 2022),

“Winners of Black Beauty-inspired Writing Competition Revealed” (Dec 6, 2023),

To learn more about the the new edition of Black Beauty, the Anna Sewell House, and Anna Sewell herself, you can listen to this audio posting from Redwings Horse Sanctuary:

And Down Some Rabbit Holes…

The Home of Rest for Horses still exists, though it has moved a number of times and changed a lot. After cabs were motorized, they cared for cart horses. During World War I, the Home took in and treated injured Army horses. After the war, they began to take in veteran Army horses. During World War II, the Home sheltered and treated horses (and other animals) injured or displaced in air raids. Renamed in 2006, The Horse Trust now focuses on the welfare of horses in general and supports scientific research and education. They take in horses that have retired from public service with the police, the military, the royal stables, and public charities, as well as neglected and abused rescues.

In Philadelphia in 1888, the first horse sanctuary in the United States, Ryerss Infirmary for Dumb Animals, was founded by a family of animal rights activists, who in 1867 had helped found the Pennsylvania SPCA. Originally located on the family’s farmland within Philadelphia’s city limits, they cared for working horses and ponies after they were too old to work. They still take in retired horses, but have had to move several times.

In 1907, the Animal Rescue League of Boston founder Anna Harris Smith bought property in Dedham as a sanctuary for Boston’s working horses and other homeless animals. The property is also a pet cemetery, Pine Ridge Pet Cemetery, which only recently stopped new burials. I wrote earlier about pet cemeteries, including this one, in “Our Sydney: Born a Dog, Lived Like a Gentleman, Died Beloved.” There is still an animal shelter at the site in Dedham.

The Animal Rescue League of Boston

In 1984 in the United Kingdom, Redwings Horse Sanctuary was started after a small group of people rescued a single pony. The charity now cares for some 1500 horses, ponies, donkeys, and mules at 11 sites across England and Scotland. They have a specialized horse hospital and a staff of 300, including equine veterinarians, nurses, behavior and welfare specialists, and farm managers. About 500 of their horses have been placed in individual homes, while Redwings provides support and retains legal ownership. I haven’t found anything comparable to it in the U.S.

One of the largest sanctuaries in the United States is Freedom Reigns Equine Sanctuary, with about 500 rescued horses living on a 4000-acre ranch in Los Gatos, CA.

Freedom Reigns Equine Sanctuary

Closer to Home

Closer to Home

In Vermont, there are about 15 rescues and sanctuaries ranging in size and mission. Horses come to these organizations for three main reasons: first, an owner needs to surrender the horse the way we surrender cats and dogs to a shelter (this may include old horses); second, the horse is seized by the police because of abuse or neglect; and third, the horse is being sold at auction and is probably headed to the slaughterhouse. In 2007, the slaughter of horses for human consumption was banned in the U.S., but the law did not expressly forbid shipping horses out of the country, to Canada or Mexico, for slaughter. Many rescue organizations seek to save these horses.

Gerda’s Equine Rescue in West Townshend rescues horses, ponies, and donkeys bound for slaughter. Since they were founded in 2005, GER has rescued, rehabilitated, and found homes for about 1000 horses.

Founded in 2012, Dorset Equine Rescue in East Dorset accepts owner-surrendered horses, ponies, and donkeys, and rescues others from kill pens and from abuse and neglect. In 2021, they went through a rigorous accreditation process with the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries. As of 2021, they had rescued, rehabilitated, and found homes for about 200 horses.

Founded in 2016, the Merrymac Farm Sanctuary in Charlotte cares for more than 100 abandoned, surrendered, or abused farm animals. They shelter about 20 horses, ponies, and donkeys; along with ducks, turkeys, chickens, rabbits, sheep, pigs, goats, and a couple of cats. In the summer of 2023, they took in two severely malnourished horses from Leicester, VT, that had been seized by the police.