Our Sydney: Born a Dog, Lived Like a Gentleman, Died Beloved

Photo: Animal Rescue League of Boston

Bee, A Loving Companion, 1874-1889. My Freddie, 1901-1918, A Noble Cat. Lady Gove, Died March 23, 1940, Sweetheart. Twinkie, 1948-1968. Beside Twinkie’s name sits a skinny outlined cat, its tail folded neatly around its feet.

I am wandering around the old section of Pine Ridge Pet Cemetery in Dedham, Massachusetts, on a cool, drizzly morning in June. I’ve never seen a pet cemetery before. Lichen has grown over some of the gravestones, so that I have to wipe it away to make out the inscriptions. A number of gravestones are tangled up in the roots of giant pines that were probably small when the animals were buried. In the distance, I can hear traffic on Route 95

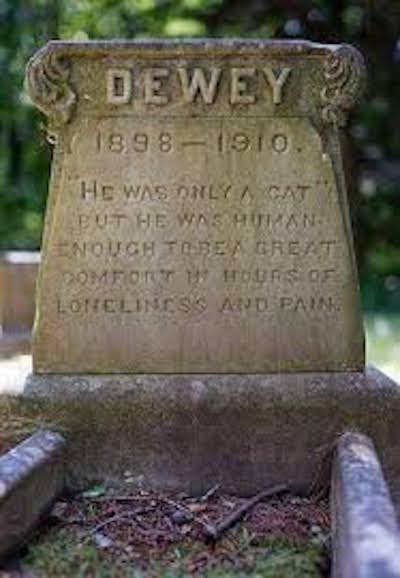

Chickaboo Lee and Irish Molly-O. Rover Birderius Brown. Pebbles and Von. Salty, Who Made Us a Family. Snoopy and Barkley, who are buried together. And there’s one of the more famous headstones: Dewey, 1898-1910. “He was only a cat but he was human enough to be a great comfort in hours of loneliness and pain.”

There are around 600 formal pet cemeteries in the United States, according to a 2009 estimate. These 600 vary from a crematory with a garden where a pet’s ashes can be spread to cemeteries like Pine Ridge. Their existence suggests that many people mourn and honor a dead pet much as they would a dead person—or at least that their feelings fall along a continuum. Is an animal property or a member of the family? Do we believe that the animal deserves dignity? Or has a soul? The boundary between humans and animals blurs a little, as the animal becomes someone, an individual.

Photo: Hartsdale Pet Cemetery

In 2017, 49% half of American homes included one pet or more, according to the American Housing Survey conducted by the US Census. Estimates run much higher, up to 68%, but this is the most reliable figure. Either way, that’s millions of dogs, cats, rabbits, hamsters, parrots, guinea pigs, ferrets, and more. What do we do with their bodies after they die? Put them out with the trash? When I was a kid, we dug holes and buried our dead pets in the yard and marked their graves with stones. But most people can’t do that. It’s a practical problem, even an environmental one. More to the point, it’s an emotional one.

One of our cats, Opus, is buried among guinea pigs, hamsters, pygmy hedgehogs, and other cats in the pet cemetery at the pre-school my sister and brother-in-law ran for many years. Each spring, crocuses come up on his grave. The ashes of the rest of our cats and dogs from the last twenty-some years—Taxi, Bear, Ruby, Bailey, and Hazel—are in a small collection of tins on a shelf in our mudroom. We still haven’t figured out what to do with them.

When I first heard of pet cemeteries, my reaction was: Are you kidding?! I assumed these cemeteries were strictly American and dated from the 1960s and later. I pictured dog- and cat-sized coffins lined with satin, plastic flowers, brightly colored banners, stuffed toys, lavish ceremonies, and a whole industry dedicated to turning people’s grief into cash. Americans spend a lot on our pets—$72.5 billion on all goods and services in 2018, according to the American Pet Products Association—so there’s clearly a market.

In fact, all the things I imagined do exist, and more: pet obituaries, online memorials, engraved glass ornaments, condolence cards, crematories, ossuaries, remembrance gardens, National Pet Memorial Day (the second Sunday in September in the US, the first Sunday in October in Poland), online support communities, and taxidermy. It’s a global gumbo of love, sorrow, goofiness, tenderness, irony, ingenuity, and commercialism. There are enough pet cemeteries that there’s even an industry association, the International Association of Pet Cemeteries and Crematories, with certification and an appropriately euphemistic name for the services they provide, “pet aftercare.”

In counterpoint to the commercialism, a campaign has been launched in this country to ensure that pet burials are green and coffins biodegradable. And there’s a small movement to allow pets to be buried in human cemeteries in the family plot or the same grave. A few cemeteries even permit it, or create a pet section.

Humans buried animals for thousands of years.Our modern pet cemeteries are the most recent expressions of an ancient impulse. The earliest known animal burial, of a fox with a person, took place 16,500 years ago in the oldest cemetery in the Middle East, in what is now Jordan. Over 14,000 years ago, a seven-month-old puppy was buried with a man and a woman, along with grave goods, in northern Europe. Recent reexamination of the remains (part of a jaw and some teeth) reveal that the dog, known as the Bonn-Oberkassel dog, discovered near Bonn in 1914, had been seriously ill for some time. For it to survive even seven months took human effort and care. The authors of the study suggest that this may reveal more than a utilitarian human-animal relationship, but an emotional one. Around 12,000 years ago in present-day Israel, a person was buried with a puppy, and one of the person’s hands was laid on the puppy’s body. Around 8,000 years ago, dog burials, usually alongside a human, became common. In the present-day southeastern United States, from 8,000 to 3,000 years ago dogs were routinely buried. It was so common, John Bradshaw notes in Dog Sense, “that it is their relative infrequency from laterburial grounds that archaeologists feel they need to explain, rather than the other way around.”

Why did so many ancient humans bury animals, especially their dogs? As hunter-gatherers, we lived close to animals and respected them. Humans hunted and were hunted; we were only one animal among many, and not particularly tough. When dogs became our hunting companions, they increased our tracking ability, speed, and power. Then, as we became herders, dogs guarded and guided our flocks and herds. Dogs may well have made the domestication of some of these species possible. Perhaps ancient burials honored dogs’ role in our survival. Or recognized our emotional bond.

The dogs buried with people, however, must have been sacrificed. That’s a painful twist from my contemporary point of view. What did that sacrifice mean? Was the dog a gift, guide, or companion for the dead? It’s impossible to know.

As humans used animals and plants to construct an ecological niche and better control our destiny, our attitude toward nature changed. Genesis, the creation story of a pastoral people, exhorted us to subdue “every living thing” and exert dominion over sea, air, and land. The new relationship, Leslie Irvine observes in If You Tame Me, included “both an intimacy with the natural world and a conquering attitude toward it.”

Human relations with animals have always been full of stark contradictions. Domestic animals were tools—to be worked, milked, shorn, slaughtered, eaten—but people knew their animals as well as they knew their neighbors. They understood the temperaments, abilities, and intelligence of individual horses. They knew the quirks and laying habits of their chickens. And almost universally, people kept some animals as pets. They lived with them and—though we should be wary of projecting our experience onto the past—may have loved them. The ancient Greeks were mad for lap dogs. The Romans slaughtered wild animals gruesomely and in great numbers for entertainment, but treasured pets. The emperor Hadrian erected a grand mausoleum for his dogs.

The Romans carried their affections for pets (and the pets themselves) to the edges of the empire. Near Leicester, England, the skeleton of a dachshund-size dog was found in a Roman-era human-size grave, laid out right in the middle. In an ancient dump outside another Roman fortified town, archaeologists unearthed a cat, in a miniature mausoleum built with roof tiles. There’s such tenderness in this scene: a person builds a tiny shelter in the middle of a dump and lays a cat’s body there.

But after the Romans, there is a fifteen-hundred-year gap in pet burials in the West. Why the gap?

The answer has got to start with our anthropocentrism: Humans claimed the center of the universe. Animals were defined as other and inferior, existing on the other side of a hard-and-fast boundary. First argued in Greek and Roman philosophy, this hierarchy and boundary were codified as God’s will and enforced by the Church, especially from the 12thcentury forward. The Church’s attempts to stamp out heresy under the Inquisition affected all aspects of daily life, including people’s relationships with the animals around them. Animal otherness confirmed human exceptionalism, their evil our virtue, their inferiority our superiority, their brutishness our humanity. European colonists carried these attitudes to the edges of new empires.

Nevertheless, in 1896, the first modern pet cemetery came into being.When a woman who lived in New York City lost her dog and wanted to bury it, she had no idea what to do. A veterinarian, Samuel Johnson, offered her a spot in his apple orchard in Hartsdale, just north of the city. It was a simple act of kindness, but turned into something remarkable. He mentioned the burial to a friend, who wrote it up as a human-interest story. Then requests poured in, as New Yorkers asked to bury their dogs on his land. Sydney, the beloved gentle-dog of this article’s title, died September 4, 1902, and is buried there.

Dr. Samuel Johnson. Photo: Hartsdale Pet Cemetery.

In 1905, Johnson set aside three acres and, in 1914, legally incorporated the Hartsdale Canine Cemetery—now Hartsdale Pet Cemetery. In 1923, a War Dog Memorial was placed there, dedicated to the many dogs who had served in World War I. Over the years, as many as 80,000 animals have been buried there, including dogs, cats, birds, and even a lion cub. Pet owners can also choose to have their own ashes buried there, bringing humans and animals full circle.

The timing was no accident. The creation of Hartsdale Canine Cemetery depended on economic changes: a growing city with nowhere to bury pets and a growing middle class with money not only to keep pets but to pay for cemetery plots.

It also depended on cultural changes that had been gathering momentum for some time, especially renewed philosophical and theological debates about the nature of animals. In the 17thcentury Descartes had defined animals as soulless machines and practiced vivisection on them, but the scientific revelations made possible by his cruel experiments helped undermine his assumptions. Animals and humans were anatomically and physiologically similar, so it became clear that animals suffer the way humans do. Philosophers, theologians, and ordinary people wondered: How can an all-powerful, merciful God allow the innocent to suffer? They began to apply Christian ethics to animals and believed that people had an obligation to treat them with compassion.

In the 19thcentury, even before Darwin challenged human exceptionalism directly with The Origin of Species, animal welfare movements started. In 1822, the first animal protection law was enacted in Great Britain, and laws followed soon after in Germany. In 1824, the first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was founded in Britain. In 1845, a similar organization was founded in Paris. Animal welfare organizations in the United States came into existence within the deep shadow of slavery. The movement started after the war, in 1866, with the creation of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the passage of the first anti-cruelty law.

The animal protection groups faced painful questions: Did they value animals over people? What about sweatshops?

For a time, animals had more legal protection from their owners than children had from their parents and guardians. In a famous 1874 case of child abuse involving 10-year-old Mary Ellen McCormack, it was the ASPCA who took up her cause and helped remove her legally from her home. Later that same year, Henry Bergh, a founder of the ASPCA, and others created the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. In 1877, following a meeting of many animal welfare organizations, American Humane was founded with a double mission: to protect both animals and children.

Pet cemeteries exist in many countries.The second modern pet cemetery, Le Cimitiere des Chiens—now Le Cimitiere des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestiques, the Cemetery of Dogs and Other Domestic Animals—was established in a suburb outside Paris in 1899. Some claim that it’s really the world’s first modern pet cemetery, which may be technically true since Hartsdale Canine Cemetery developed so slowly.

Many more pet cemeteries were created outside cities, mostly in the U.S. and Western Europe, in the second half of the 20thcentury. The International Association of Pet Cemeteries and Crematories, founded in 1971 to set business standards, now has members in the United States and fifteen other countries, including Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, South Africa, and Australia. (I can’t imagine they’re the only such organization.) Japan, with long traditions of showing respect to the souls of animals that have been hunted or slaughtered, has as many as 900 pet cemeteries. In South Korea, in addition to having pet crematories and ossuaries, Buddhist temples conduct services for animals killed in slaughterhouses and by cars on the roads. In Poland, the first pet cemetery was founded outside Warsaw in 1991, and as of 2014 there were eleven official pet crematories and cemeteries in the country.

In 1899, Anna Harris Smith organized the Animal Rescue League of Boston, based on her belief that “kindness uplifts the world.” She wanted to address pet abandonment, the abuse of work horses, and the inhumane transport of livestock. She used her land in Dedham, southwest of the city, as a summer sanctuary for Boston’s work horses. Pine Ridge Pet Cemetery, founded in 1907, along with the Animal Rescue League’s shelter and adoption center, now occupies that property.

When I visited on a Monday, the adoption center was closed and the place quiet. I drove past barn-red buildings and an empty corral. A rooster wandered across the parking lot and briefly followed me among the gravestones. Once I was deeper into the old section of the cemetery, I was startled by a wild turkey and her three chicks. Under huge oaks, maples, and white pines, I found Twinkie the cat and Von the dog. The oldest grave I saw, a flat two-foot by three-foot stone, belongs to Bee. Since the grave predates the cemetery by 18 years, I suspect Bee was one of Anna Harris Smith’s own pets.

My initial judgments of pet cemeteries, and the people who run them and bury their animals there, now seem anthropocentric and mean-spirited. What I thought was a superficial, modern, and American phenomenon is ancient and global. Is there really any good reason not to bury an animal?

My initial judgments of pet cemeteries, and the people who run them and bury their animals there, now seem anthropocentric and mean-spirited. What I thought was a superficial, modern, and American phenomenon is ancient and global. Is there really any good reason not to bury an animal?

References (in the order of their first appearance):

Karin Brulliard and Scott Clement. “How Many Americans Have Pets? An Investigation of Fuzzy Statistics.” The Washington Post, Jan. 31, 2019,

Margo DeMello, ed. Mourning Animals: Rituals and Practices Surrounding Animal Death.Michigan State University Press, 2016.

This collection of essays covers a range of topics: Hartsdale Pet Cemetery (in a photo essay), ancient burial practices, the formation of Christian animal ethics in Britain, animal mourning practices and cemeteries in other countries, and more. I drew on DeMello’s introduction for the broad background and on essays by Liza Wallis Margulies, James Morris, Alma Massaro, Michel

Piotr Pregawski, and Elmer Veldkamp for more detailed explorations.

American Pet Products Association. “Pet Industry Market Size and Ownership Statistics.” americanpetproducts.org.

Luc Janssens, et al. “A New Look at an Old Dog: Bonn-Oberkassel Reconsidered.” Journal of Archaeological Science, April, 2018,

John Bradshaw. Dog Sense. Basic Books, 2011.

Leslie Irvine. If You Tame Me. Temple University Press, 2004.

James Serpell. In the Company of Animals. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Hartsdale Pet Cemetery, hartsdalepetcrematory.com.

Howard Markel. “Case Shined First Light on Abuse of Children.” The New York Times, Dec. 14, 2009, nytimes.com.