Your Guess Is as Bad as Mine

As Zola accepted pats from a group of little kids, one of the parents asked, “What kind of dog is she?”

As Zola accepted pats from a group of little kids, one of the parents asked, “What kind of dog is she?”

“German shepherd mix.”

He tilted his head and studied her. “Yeah, I can see that.”

If you own a dog, especially a mutt, you’ve had a conversation—or fifty—like this. Your dog is a conversation starter, a way for other people who like dogs to connect with you. Social scientists have a term for it: Your dog’s a social lubricant. Bizarre phrase, right? But true.

I think something else is going on here, too, something we barely notice. We want to identify what kind of dog we’re looking at, to find the right category, to figure something out. A mutt’s a puzzle to solve and a story to tell, and both are fun. Based on the breed or breeds, we also believe we know something about a dog and can explain its behavior. That belief’s very human.

Like Zola, most dogs in the US are mixed breeds. I’ve seen estimates of 53% and 54%, and some run much higher. This percentage has risen, according to the American Veterinary Medical Association, as more and more people get their dogs from shelters and rescue groups rather than breeders. We’re not using AKC pedigrees when we fill out the paperwork at the vet’s or city hall. We’re eyeballing our dogs. And we often list a predominant breed.

It turns out that what we write down is more likely to be wrong than right. Which means that our assumptions that we know something about our dogs are also wrong.

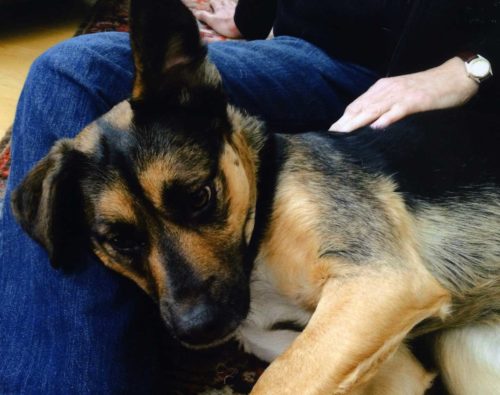

We adopted Zola in 2015. On the rescue group’s website, she was labelled a shepherd mix. With her tan-and-black markings, dark face and expressive eyebrows, coat length and texture, and long legs and toes, Zola looks the part—only minus the regal bearing of a German shepherd. She’s clearly a mix: she weighs in at 45 pounds rather than 50-70; her muzzle is shorter and narrower than a shepherd’s; her ears fold over; and her hips don’t drop but ride a bit high.

My wife and I had some history with rescue dogs and had ideas about our next dog. In 2001, we’d adopted a big hound-type dog. Toby had a gentle disposition, but all he wanted to do was run. No matter what collar we used—training, choke, even prong—and no matter how much training we did, walking him was like waterskiing on land. He was also food obsessed. Eating dinner was like putting on a show with an audience of one. On high alert, Toby sat a few feet away, a long line of drool running from his mouth and puddling on the floor, and followed every forkful. Bit by bit, he scooched forward. Getting him to stay back and not put his snout right on the table, which was right at chin level, took a lot of work. After seven months, we called it quits and found him a new home with a couple of easygoing young people who let him run and eat all he wanted.

A little over a year later, we lucked into a great six-year-old dog from our local shelter. She was a registered golden retriever, but because of her age she came with a senior discount. Walking Bailey was a dream: she trotted contentedly about 15 feet in front. She loved to walk, but once inside the house flopped on her bed. In 2015, we were hoping for a dog we could easily let off leash, a shepherd or retriever type (not a hound), who would either round us up or stay close by like Bailey.

At our first visit, our veterinarian said “beagle mix.” At least, that’s what I remember. Later, we saw “hound mix” written on her record.

Beagle?! Hound?! Shoot, we’d gotten a hound after all.

As we got to know Zola better, we added terrier to the list because she hunts tenaciously and roots out voles, mice, and chipmunks. We wanted to find the right categories, to know what kind of dog she was. We settled on German-shepherd-beagle-and-maybe-some-terrier. In spite of what our vet had said, we kept putting shepherd first. She just looked like a shepherd.

This is the story we told ourselves and anyone who asked. Over a couple of years, it morphed from hypothesis to fact.

When I was doing some reading about dogs in 2018, I realized we were probably wrong. Almost certainly wrong. Our vet was almost certainly wrong, too. The mix-and-match method of breed identification—like those games that shuffle noses, eyes, mouths, and chins—doesn’t cut it.

Some researchers had noticed that dog professionals frequently labeled the same mixed breed dog differently and wondered what was going on. Their 2009 study focused on the “predominant breed” labels assigned by adoption agencies to help people like us make decisions. They used 20 mixed-breed dogs that had been adopted from 17 different rescue organizations. They took blood samples and ran their DNA. The upshot? The breed labels were wildly off. Sixteen of the 20 dogs had been assigned a predominant breed label, but only four had DNA markers to match—and three of those four dogs had as many markers for other breeds as they did for the named breed.

The visual identifications of the predominant breeds were wrong over 90% of the time (see the poster here). For example, one dog was adopted at five years old as a cocker spaniel mix. Based on the photo, I can see why, but DNA analysis revealed 25% each of Rottweiler, American Eskimo dog, golden retriever, and Nova Scotia duck-tolling retriever. My favorite case of mistaken identity is the “shepherd mix” with 25% Lhasa Apso and 12.5% each of Bichon Frise, Australian cattle dog, Italian greyhound, Pekingese, and Shih Tzu.

The outcomes of the study were so compelling that the researchers advised adoption agencies to stop making visual identifications. My local humane society now simply uses “American Shelter Dog.”

It’s kind of a funny name, though. What kind of dog do you have?

Oh, um…an American Shelter Dog.

A what?

The researchers conducted a bigger study in 2013. They used the same 20 dogs, but worked this time with over 900 dog professionals—veterinarians, vet techs and assistants, trainers, animal behaviorists, shelter workers, animal control officers, dog breeders, groomers, and even a few dog show judges. They had two questions: How often would the visual identifications match the DNA analysis? And how often would the respondents agree with one another about the identifications (this is called inter-observer reliability)? They gave each person a one-minute color video of each dog, with information about the dog’s sex, weight, and age, and asked them to identify the dog’s breed or breeds.

There was “wide disparity” between the visual and DNA identifications and “a low level of agreement among people regarding breed composition.” For 14 of the 20 dogs, fewer than 50% of the people made identifications that matched the DNA analysis. For only seven of the 20 dogs did more than 50% of the respondents agree with one another on the predominant breed, and in three of those seven cases the most common visual identification did not match the DNA. Remember, these are people who know dogs, who work with dogs every day. Subsequent studies have yielded similar results. Why do even dog professionals get this so wrong?

It’s the genetics, of course. Out of 20,000 to 25,000 genes, fewer than 1% of them determine a dog’s looks: the shape of its ears, its overall size, its coat length and coloring, the size and shape of its skull and muzzle. This is surprising, since there is more physical variation within the species than any other on the planet—think Newfoundlands and Chihuahuas—but apparently breeders have been working with only a tiny slice of the genetic pie.

Appearance is a reliable marker in purebred dogs (though even some breeds are hard to tell apart) because those dogs have been selected for their appearance for many generations. Dogs used to be purpose-bred for work—a great pointer was crossed with another great pointer, no matter what they looked like—but most breeds are now bred for their looks, or conformation to an ideal appearance. The gene pool is closed and all diversity systematically excluded. A pedigree proves that a dog is inbred and has been inbred over time. Though we discourage inbreeding for humans, we value it for dogs—with some predictable consequences (hip dysplasia, for example) if breeders aren’t careful.

But as soon as you open up the gene pool, the dog’s natural genetic diversity comes back into play. A mixed breed dog’s phenotype (its appearance) doesn’t necessarily match its genotype (its genetic makeup). One parent can be a purebred cocker spaniel and the other a mutt, but their puppy looks nothing like the cocker spaniel, or the mutt for that matter. Conversely, only one great grandparent can be a basenji, but its great grand-puppy looks an awful lot like a basenji—though its predominant breed is actually standard schnauzer. Janis Bradley, a researcher and writer who works with the National Canine Research Council, states unequivocally, “we cannot attribute ‘predominant breed’ identification to any dog based on appearance, not matter how striking the resemblance.”

Siblings Bruno and Moka. Bruno is about twice the size of Moka.

Okay, so maybe Zola wasn’t a German shepherd mix (or a hound) after all. It was time for a DNA test. This is like the testing done by Ancestry.com or 23andMe, only for dogs.

After checking out companies and reviews, I homed in on two, Orivet and Wisdom Panel. The test’s not 100% accurate but more like 90% for the first generation cross. Plus, the further back you go in the dog’s family tree, the harder it is to track breeds. I sent Zola’s DNA to Orivet first. Emily, who’s skeptical, thought we should use both companies—and check their work, so to speak. So I sent Zola’s DNA to Wisdom Panel, too.

It’s an easy process. You sign up and pay on line (recently, I’ve seen Wisdom Panel packages at the pet food store), and they send a kit. It includes two cheek swabs—tiny versions of the cylindrical brush you’d use to scrub out a jar—along with instructions, plastic sleeves and labels for the samples, and a return envelope. Zola only squirmed a bit when I rolled the brushes inside her cheek.

The results come over email a few weeks later. The two companies agreed: No shepherd, no beagle, no hound. Zola’s predominant breed is Siberian husky at 25%, and 12.5% each rough collie (like Lassie), Dalmatian, and Rottweiler. This means that Zola had one purebred husky grandparent; and her great grandparents’ generation included one purebred Dalmatian, one collie, and one Rottweiler along with two purebred huskies.

Here’s a sobering realization for me. If Zola’s breed label had accurately read “Siberian husky mix,” I might have shied away from adopting her, since huskies have a reputation as stubborn and hard to train. That would have been a big mistake.

Dalmatian was the most surprising discovery—but, then, the breed never even crossed my mind as an option. (That’s one problem of course: we guess what’s familiar.) The only Dalmations I know are from the film. Shouldn’t all Dalmatian mixes have some spots? (No.)

This still leaves 37.5% of Zola’s makeup unaccounted for. Orivet left it blank. Wisdom Panel listed three “likely” breed groups—herding, terrier, and sporting—in the order of their likelihood. That’s hardly definitive.

Now, when someone asks what kind of dog Zola is, I say Siberian husky mix. Nobody says, “Yeah, I can see that.” Sometimes, if the person seems interested, I’ll explain. The only breed anyone “sees” is the Rottweiler.

Probably, I should simply say “mutt” since over a third of her DNA is so mixed that it can’t be sorted out. But I don’t. I still suffer from some kind of breed bias. It could be that, growing up around so many purebred dogs in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, when all across the country middle-class suburban families like ours were getting German shepherds, collies, cocker spaniels, and golden retrievers, I expect a dog to be shaped, in body and character, by breed—somehow, some way.

But Zola’s simply herself: Sometimes skittish, pretty cuddly, kind of stubborn, approachable yet shy, not particularly eager to please, playful, fruit-and-berry-eating, gentle (unless you’re a squirrel or a vole), independent, sweet-natured, and generally easygoing. If you’re a stranger, she may approach you and then duck away. But if you sit down on the floor or ground, she’s likely to climb into your lap.

Zola did this the day we first met her, even though she had been a stray.

What does this mean for you if you own a mixed breed dog?

One answer is don’t assign a breed label to your dog, even if it looks strikingly like a basenji. Or a German shepherd! When asked to fill out paperwork, write “mixed breed.”

Another answer is don’t rely on breed labels. Victoria Voith, the lead author for both studies I’ve described here, recommends: “If anybody is missing a dog, go to the shelter and look for it personally” because your breed identification and theirs probably won’t match.

Finally, don’t rely on breed stereotypes. Treat your dog as an individual with her own character and behavior. Even the Wisdom Panel website insists on this. After touting the distinctive qualities of each breed, they add: “All dogs should be considered individual animals. Because each is a product of their unique environment and handling, they may exhibit different traits and behaviors than those listed here.”

References (in the order of their first appearance):

United States Pet Ownership and Demographics Sourcebook, 2012. American Veterinary Medical Association, avma.org.

Voith, V.L., E. Ingram, K. Mitsouras, & K. Irizarry. “Comparison of Adoption Agency Breed Identification and DNA Breed Identification of Dogs.” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 12:3 (2009), 253-262.

Voith, V. L., R. Trevejo, S. Dowling-Guyer, C. Chadik, A. Marder, V. Johnson, & K. Irizarry. “Comparison of Visual and DNA Breed Identification of Dogs and Inter-Observer Reliability.” American Journal of Sociological Research 3:2 (2013), 17-29.

Bradley, Janis. The Relevance of Breed in Selecting a Companion Dog. National Canine Research Council Vision Series Publication, 2011, nationalcanineresearchcouncil.com.

“Visual Breed Identification: Interview with Dr. Victoria Voith on the Inaccuracy of Visual Dog Breed Identification.” National Canine Research Council, 2010, nationalcanineresearchcouncil.com.

These last four references come from the website of the National Canine Research Council, an organization dedicated to using high quality research from leading researchers around the world to make informed recommendations about public policy. Their carefully selected research library includes academic articles on visual breed identification. You can find summaries and links to the articles. Check out their website.